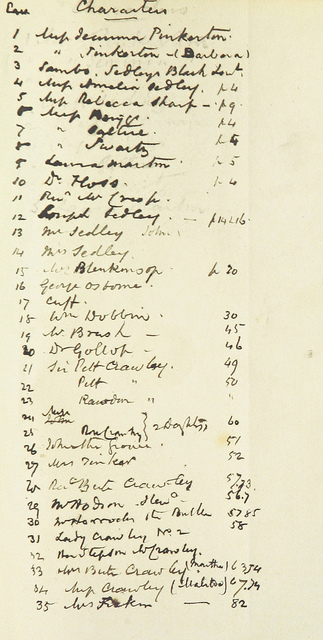

Two weeks ago we sent out a call to fans of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, to come answer a survey on how they rate the importance of the characters in the novel. And the results are in!

While we’re not going to release the full list of rankings just yet, I can assure you all that we can now say with confidence, for the first time in literary history*, who the main characters in Pride and Prejudice are. And readers of the novel may be shocked and appalled to discover that…

…they’re exactly who you’d expect. So we’re not even going to talk about them. We are, however, going to look at the exact opposite end of the scale: the least recognisable figures in the novel. This is because the most common response from the kind, Austen-loving members of the public who filled out our survey was that they didn’t remember half of these people, even though they had thought they were very familiar with P&P, and now they’re starting to question everything they hold dear.

Fear not, good readers! You haven’t been accidentally reading the abridged version all these years – it’s just that some of the characters on our list are very obscure indeed.

So who are all these people?

When we started out constructing social networks of characters from our collection of 19th century novels, we realised quite quickly that most of these books contain a huge number of characters who might not make a massive impression on the plot, but are present in the background – the literary equivalent of extras. We considered ignoring these characters and focusing on the main cast, but determining which characters to include and which to leave out turned out to be a difficult and inexact task, especially in a corpus of very diverse works. And to cut a long story short, we realised we liked our extras, and wanted to know more about them.

So if you filled out our reader survey and are fairly sure you didn’t come across 117 people in Pride and Prejudice last time you read it, this is because when we compiled that list, we added every last entity that could possibly be considered a character. In fact, Pride and Prejudice has a small, cast of characters, compared to certain of our other novels. Ever wanted to know the population of Middlemarch, for example? By our reckoning, it’s the tidy figure of 333! (Admittedly, some of them are goats.)

Meanwhile, in Vanity Fair… actually, I’m still not ready to talk about Vanity Fair. I may not ever be ready to talk about Vanity Fair.

So without further preamble, here are the top five Pride and Prejudice characters that are most likely to make you say: “Who?”

5. Your Maid

Servants abound in nineteenth-century novels, and Pride and Prejudice is no exception. While the cohort of servants in our corpus is a very large one – we’ve counted over 600 servants so far – and they are very often present in the background of scenes, they tend not to attract much attention in literary research. However, one of our reasons for wanting to include as wide a field of characters as possible was to create social networks that represented the complexities of social class in the same way that the novels themselves do, rather than to just let them fade quietly into the background (as many of the aristocrats in these works would no doubt prefer them to do). That’s why even this unnamed maid, who’s mentioned just once in the novel, has been listed here.

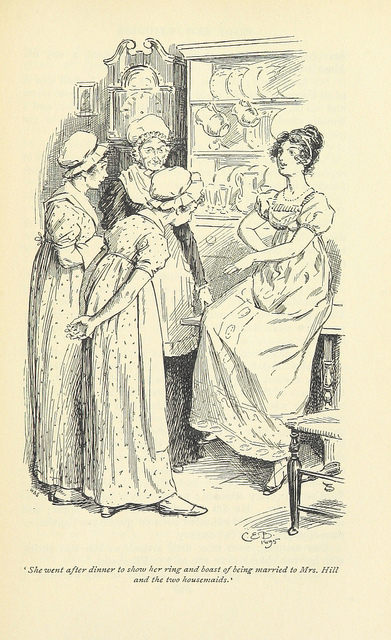

As it happens, Pride and Prejudice, despite being primarily about the activities of middle-to-upper-class people, takes a fair amount of interest in servants. Their opinions are noticed (“What praise is more valuable than the praise of an intelligent servant?”) and quite a few of them are named, including Mrs. Hill, the Bennets’ housekeeper, who is of course a mainstay of the Longbourne household.

Mrs. Reynolds, the Pemberley housekeeper who plays a pivotal role in changing Elizabeth’s mindset about Mr. Darcy, her employer, is another important and high-ranking servant. Readers might be less likely to remember the name of the Netherfield Park housekeeper – but I can guarantee that she’s named in the novel. (Know who she is? Answers in the comments!)

Lower-status servants, however, don’t always get names – particularly when they’re employed in small, unpretentious establishments like the inn at Lambton.

On his quitting the room [Elizabeth] sat down, unable to support herself, and looking so miserably ill, that it was impossible for Darcy to leave her, or to refrain from saying, in a tone of gentleness and commiseration, “Let me call your maid. Is there nothing you could take to give you present relief? A glass of wine; shall I get you one? You are very ill.”

4. Your Great Uncle the Judge

At the other end of the social scale, we have an eminent but deceased member of the Darcy family. This judicial uncle is mentioned by Caroline Bingley, who’s making jokes to Mr. Darcy about the possibility of his marrying into the Bennet family:

“Have you anything else to propose for my domestic felicity?”

“Oh! yes. Do let the portraits of your uncle and aunt Phillips be placed in the gallery at Pemberley. Put them next to your great-uncle the judge. They are in the same profession, you know, only in different lines.

Caroline is killing three birds with one stone, in this conversation:

- emphasising her knowledge of Darcy’s illustrious family background (I’m so interested in you and your family! Because they’re great! Say, have I told you lately that you’re great?),

- making fun of a possible romantic rival (Elizabeth’s family are terrible though, amirite), and

- calling attention to the shortcomings of the Bennets’ connections in order to distract from her own perhaps not-so-aristocratic origins (say, how about we don’t talk about the fact that my family’s fortune was acquired through trade?)

This method of fascinating and alluring a wealthy gentleman obviously has some drawbacks.

3. The Two Elegant Ladies Who Waited On His Sisters

These two elegant ladies are the “abigails” of Caroline Bingley and her sister Louisa Hurst, and are presumably responsible for the curation of the sartorial details (such as “the lace on Mrs. Hurst’s gown”) that make the sisters so impressive to the ladies of Meryton. I don’t believe I’ve ever seen them cast in a screen adaptation, which is a bit of a shame; they’re no doubt essential to the Bingley household, and it would be intriguing to see how a costume department would present these two intimidatingly fashionable servants.

We meet the elegant ladies on the morning after Elizabeth comes to Netherfield to stay with her ailing sister Jane:

Elizabeth passed the chief of the night in her sister’s room, and in the morning had the pleasure of being able to send a tolerable answer to the inquiries which she very early received from Mr. Bingley by a housemaid, and some time afterwards from the two elegant ladies who waited on his sisters.

This short scene gives a surprising amount of insight into the workings of Netherfield Park. Bright and early in the morning, Mr. Bingley sends a housemaid as an emissary to the room of his sick guest in order to find out how she’s doing; after all, no matter how anxious he is, it wouldn’t be appropriate for a gentleman to barge into a lady’s chamber. Later on in the day, however, when Caroline and Louisa eventually remember that Jane is staying with them (or perhaps they’ve just had a bit of a lie-in), they send their maids as messengers rather than go to visit her themselves. This might be to emphasise the contrast between their brother’s concerned interest and their own indifference, but it’s equally likely that the two ladies, who (we’re told) spent an hour and a half of the previous evening dressing for dinner, are not quite dressed and ready to be seen about the house just yet.

2. General 1

This entry on the survey seems to have been a bit misleading, and might have caused our respondents some confusion. We’d like to apologise for this. The character’s name doesn’t appear exactly in this format in the book, but the coy notation used in the original doesn’t agree very well with our processing software.

The anonymous General appears toward the end of the novel, in a letter from kind Uncle Gardiner to Mr. Bennet clarifying the future plans of his new and unsatisfying son-in-law:

It is Mr. Wickham’s intention to go into the regulars; and among his former friends, there are still some who are able and willing to assist him in the army. He has the promise of an ensigncy in General ——’s regiment, now quartered in the North. It is an advantage to have it so far from this part of the kingdom. He promises fairly; and I hope among different people, where they may each have a character to preserve, they will both be more prudent.

We know practically nothing about this military man, except that he’s based conveniently far away and is foolhardy enough to employ Wickham. However, though we learn at the end of the novel that the Wickhams are not an enormous social or financial success, he is only discharged from the army “when the restoration of peace dismissed them to a home”, so we assume he must not have been a total failure in the regiment of General Blankety Blank. Huzzah!

And finally, the man you all had no recollection of:

1. Haggerston

This gentleman, who is actually mentioned twice in the novel, is in fact Mr. Gardiner’s solicitor. He serves a small but vital function: seeing to the administrative side of hushing up Lydia’s elopement and rather delayed (whoops!) marriage to Wickham.

Mr. Gardiner writes to Mr. Bennet to thrash out the details of the union between the lovebirds:

All that is required of you is, to assure to your daughter, by settlement, her equal share of the five thousand pounds secured among your children after the decease of yourself and my sister; and, moreover, to enter into an engagement of allowing her, during your life, one hundred pounds per annum…If, as I conclude will be the case, you send me full powers to act in your name throughout the whole of this business, I will immediately give directions to Haggerston for preparing a proper settlement.

Even under the most irregular of circumstances, one must do these things properly.

—

*This claim may not stand up to any kind of scrutiny.

The housekeeper at Netherfield is named “Nicholls.” Bingley says in chapter 11, “as soon as Nicholls has made white soup enough, I shall send round my cards.”

LikeLike